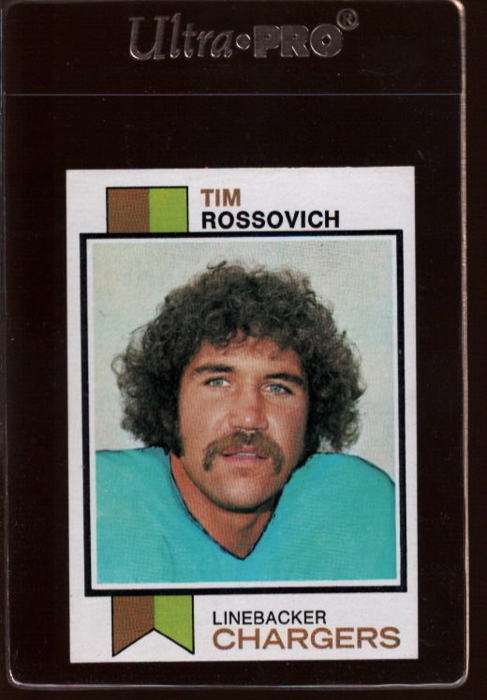

Tim Rossovich was an All-American defensive end in college at USC and an All-Pro defensive end during his second season in the NFL. The following year, his Philadelphia Eagles coach requested that Rossovich switch to the middle linebacker position for the benefit of the team. The mercurial Rossovich didn’t hesitate. He agreed, with enthusiasm.

Rossovich built a reputation as a madcap oddball willing to do and say anything in order to attract attention (a classic example of his craziness involves the time he entered his customary local watering hole. Rossovich had a fresh plaster cast on his right arm and told the regulars that he broke his arm during practice, earlier that day. His fans consoled him and the discussion turned to the Eagles’ fortunes. In the midst of the conversation, Rossovich became incensed. He jumped off his bar stool and smashed his arm, the one in the cast, into the bar. Then he slammed the same arm into a chair, reducing the chair to splinters and cracking the cast. He swung his arm in haphazard arcs, hammering away at objects until the cast was reduced to just a few scant particles. The onlookers stared, speechless and in amazement. Rossovich wiped the remainder of the plaster from his arm, then flexed his arm. “It’s healed! It’s a miracle!” No one there had any idea if the arm was ever broken, or not). At his essence, Rossovich was an unrestrained, if overgrown, innocent child who loved everything about football.

“{He} would practice all day and all night if I wanted him to,” said his coach. Rossovich practiced the same as he played the games and the same as he lived: unrestrained, uninhibited, and unconcerned about consequences. Most fans, and many teammates, loved him because he wore his proverbial heart on his sleeve and played with a joy and passion often missing in his pro sports contemporaries. When he hit the tackling sled during practice he tried to crush the metal and annihilate the frame. He stood up and tackled the sled over and over again until the coaches had to physically restrain him and coax him to let someone else have their turn. He hit someone as hard as possible on every play, even if it sometimes was his own teammate because the whistle had already blown and the play was officially over and he didn’t want to draw a penalty.

He yelled across the line of scrimmage to running backs and quarterbacks. “I love you, man, but I gotta wipe you out!” He did not have an off switch; if he was on a football field he hit and he scratched and he clawed and he fought before, during and after each whistle. His motor was in a constant state of overdrive with a full turbo-charge boost. He had the quintessential linebacker mentality.

Dick Butkus was considered the greatest middle linebacker in football, so Rossovich became an incessant watcher of a Butkus highlight film. He even made his teammates watch the film before games. In the film, Butkus waxes ecstatic about tackling quarterbacks and obliterating offenses. He speaks about tackling with such conviction that church groups and Cub Scout organizations called the makers of the film and staged a national protest, decrying the unabashed glee and the unrepentant violence. Rossovich lamented that he hadn’t played linebacker sooner! He wanted to eclipse Butkus and become known as the greatest linebacker in football.

Alas, for all his preparation and devotion, Rossovich was beset by injuries and never became a star on the level of his idol, Butkus. Rossovich did his best and never held back from full effort, but stardom eluded him. He didn’t care, he thought it was cool. “… Nobody’s wrong if you go 100%. That’s what I demanded of my teammates and that’s what I demanded of myself.” His joy derived from the pursuit of his goal and not just its attainment. Some (all) call him crazy, but Rossovich had too much fun to notice. “Everything about football can make you a better person,” said Rossovich, and he always tried to be a better player and a better man. Get crazy, like Rossovich, and your story will also always be remembered.

From October 2010, http://raising-a-man.tumblr.com

Rossovich built a reputation as a madcap oddball willing to do and say anything in order to attract attention (a classic example of his craziness involves the time he entered his customary local watering hole. Rossovich had a fresh plaster cast on his right arm and told the regulars that he broke his arm during practice, earlier that day. His fans consoled him and the discussion turned to the Eagles’ fortunes. In the midst of the conversation, Rossovich became incensed. He jumped off his bar stool and smashed his arm, the one in the cast, into the bar. Then he slammed the same arm into a chair, reducing the chair to splinters and cracking the cast. He swung his arm in haphazard arcs, hammering away at objects until the cast was reduced to just a few scant particles. The onlookers stared, speechless and in amazement. Rossovich wiped the remainder of the plaster from his arm, then flexed his arm. “It’s healed! It’s a miracle!” No one there had any idea if the arm was ever broken, or not). At his essence, Rossovich was an unrestrained, if overgrown, innocent child who loved everything about football.

“{He} would practice all day and all night if I wanted him to,” said his coach. Rossovich practiced the same as he played the games and the same as he lived: unrestrained, uninhibited, and unconcerned about consequences. Most fans, and many teammates, loved him because he wore his proverbial heart on his sleeve and played with a joy and passion often missing in his pro sports contemporaries. When he hit the tackling sled during practice he tried to crush the metal and annihilate the frame. He stood up and tackled the sled over and over again until the coaches had to physically restrain him and coax him to let someone else have their turn. He hit someone as hard as possible on every play, even if it sometimes was his own teammate because the whistle had already blown and the play was officially over and he didn’t want to draw a penalty.

He yelled across the line of scrimmage to running backs and quarterbacks. “I love you, man, but I gotta wipe you out!” He did not have an off switch; if he was on a football field he hit and he scratched and he clawed and he fought before, during and after each whistle. His motor was in a constant state of overdrive with a full turbo-charge boost. He had the quintessential linebacker mentality.

Dick Butkus was considered the greatest middle linebacker in football, so Rossovich became an incessant watcher of a Butkus highlight film. He even made his teammates watch the film before games. In the film, Butkus waxes ecstatic about tackling quarterbacks and obliterating offenses. He speaks about tackling with such conviction that church groups and Cub Scout organizations called the makers of the film and staged a national protest, decrying the unabashed glee and the unrepentant violence. Rossovich lamented that he hadn’t played linebacker sooner! He wanted to eclipse Butkus and become known as the greatest linebacker in football.

Alas, for all his preparation and devotion, Rossovich was beset by injuries and never became a star on the level of his idol, Butkus. Rossovich did his best and never held back from full effort, but stardom eluded him. He didn’t care, he thought it was cool. “… Nobody’s wrong if you go 100%. That’s what I demanded of my teammates and that’s what I demanded of myself.” His joy derived from the pursuit of his goal and not just its attainment. Some (all) call him crazy, but Rossovich had too much fun to notice. “Everything about football can make you a better person,” said Rossovich, and he always tried to be a better player and a better man. Get crazy, like Rossovich, and your story will also always be remembered.

From October 2010, http://raising-a-man.tumblr.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed